Friends,

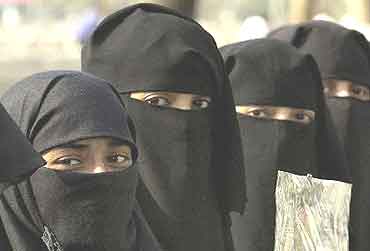

Friends,British Muslim journalist Zaiba Malik had never worn the niqab. But with everyone from Jack Straw to Tessa Jowell weighing in with their views on the veil, she decided to put one on for the day. She was shocked by how it made her feel — and how strongly strangers reacted to it.

Here is her story. She recounts being at a mosque and finding out that she was the only one in the face mask,

"At the mosque, hundreds of women sit on the floor surrounded by samosas, onion bhajis, dates, and Black Forest gateaux, about to break their fast. I look up and down every line of worshippers. I can't believe it — I am the only person wearing the niqab. I ask a Scottish convert next to me why this is. "It is seen as something quite extreme. There is no real reason why you should wear it. Allah gave us faces and we should not hide our faces. We should celebrate our beauty."

Zaiba Malik then writes about her encounter with a baby:

"At the supermarket, a baby no more than two years old takes one look at me and bursts into tears. I move towards him. "It's OK," I murmur. "I'm not a monster. I'm a real person." I show him the only part of me that is visible — my hands — but it's too late. His mother has whisked him away. I don't blame her. Every time I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirrored refrigerators, I scare myself."

Read and reflect.

Tarek

----------------------

October 25, 2006

"Even other Muslims turn and look at me"

By Zaiba Malik

The Hindu, New Delhi

[Orignally printed in The Guardian, UK]

"I DON'T wear the niqab because I don't think it's necessary," says the woman behind the counter in the Islamic dress shop in east London. "We do sell quite a few of them, though." She shows me how to wear the full veil. I would have thought that one size fits all but it turns out I'm a size 54. I pay my £39 and leave with three pieces of black cloth folded inside a bag.

The next morning I put these three pieces on as I've been shown. First the black robe, or jilbab, which zips up at the front. Then the long rectangular hijab that wraps around my head and is secured with safety pins. Finally the niqab, which is a square of synthetic material with adjustable straps, a slit of about five inches for my eyes and a tiny heart-shaped bit of netting, which I assume is to let some air in.

I look at myself in my full-length mirror. I'm horrified. I have disappeared and somebody I don't recognise is looking back at me. I cannot tell how old she is, how much she weighs, whether she has a kind or a sad face, whether she has long or short hair, whether she has any distinctive facial features at all. I've seen this person in black on the television and in newspapers, in the mountains of Afghanistan and the cities of Saudi Arabia, but she doesn't look right here, in my bedroom in a terraced house in west London. I do what little I can to personalise my appearance. I put on my oversized man's watch and make sure the bottoms of my jeans are visible. I'm so taken aback by how dissociated I feel from my own reflection that it takes me over an hour to pluck up the courage to leave the house.

I've never worn the niqab, the hijab or the jilbab before. Growing up in a Muslim household in Bradford in the 1970s and 1980s, my Islamic dress code consisted of a school uniform worn with trousers underneath. At home I wore the salwar kameez, the long tunic and baggy trousers, and a scarf around my shoulders. My parents only instructed me to cover my hair when I was in the presence of the imam, reading the Koran, or during the call to prayer. Today I see Muslim girls 10, 20 years younger than me shrouding themselves in fabric. They talk about identity, self-assurance, and faith. Am I missing out on something?

On the street it takes just seconds for me to discover that there are different categories of stare. Elderly people stop dead in their tracks and glare; women tend to wait until you have passed and then turn round when they think you can't see; men just look out of the corners of their eyes. And young children — well, they just stare, point, and laugh.

I have coffee with a friend on the high street. She greets my new appearance with laughter and then with honesty. "Even though I can't see your face, I can tell you're nervous. I can hear it in your voice and you keep tugging at the veil."

"Buried in black snow"

The reality is, I'm finding it hard to breathe. There is no real inlet for air and I can feel the heat of every breath I exhale, so my face just gets hotter and hotter. The slit for my eyes keeps slipping down to my nose, so I can barely see a thing. Throughout the day I trip up more times than I care to remember. As for peripheral vision, it's as if I'm stuck in a car buried in black snow. I can't fathom a way to drink my cappuccino and when I become aware that everybody in the coffee shop is wondering the same thing, I give up and just gaze at it.

At the supermarket, a baby no more than two years old takes one look at me and bursts into tears. I move towards him. "It's OK," I murmur. "I'm not a monster. I'm a real person." I show him the only part of me that is visible — my hands — but it's too late. His mother has whisked him away. I don't blame her. Every time I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirrored refrigerators, I scare myself.

For a ridiculous few moments I stand there practising a happy and approachable look using just my eyes. But I'm stuck looking aloof and inhospitable, and am not surprised that my day lacks the civilities I normally receive, the hellos, thank-yous and goodbyes.

After a few hours I get used to the gawping and the sniggering, am unsurprised when passengers on a bus prefer to stand up rather than sit next to me. What does surprise me is what happens when I get off the bus. I've arranged to meet a friend at the National Portrait Gallery. In the 15-minute walk from the bus stop to the gallery, two things happen. A man in his 30s, who I think might be Dutch, stops in front of me and asks: "Can I see your face?"

"Why do you want to see my face?"

"Because I want to see if you are pretty. Are you pretty?"

Before I can reply, he walks away and shouts: "You tease!"

Then I hear the loud and impatient beeping of a horn. A middle-aged man is leering at me from behind the wheel of a white van. "Watch where you're going, you stupid Paki!" he screams. This time I'm a bit faster.

"How do you know I'm Pakistani?" I shout. He responds by driving so close that when he yells, "Terrorist!" I can feel his breath on my veil.

Things don't get much better at the National Portrait Gallery. I suppose I was half expecting the cultured crowd to be too polite to stare. But I might as well be one of the exhibits. As I float from room to room, like some apparition, I ask myself if wearing orthodox garments forces me to adopt more orthodox views. I look at paintings of Queen Anne and Mary II. They are in extravagant ermines and taffetas and their ample bosoms are on display. I look at David Hockney's famous painting of Celia Birtwell, who is modestly dressed from head to toe. And all I can think is that if all women wore the niqab how sad and strange this place would be. I cannot even bear to look at my own shadow. Vain as it may sound, I miss seeing my own face, my own shape. I miss myself. Yet at the same time I feel completely naked.

The women I have met who have taken to wearing the niqab tell me that it gives them confidence. I find that it saps mine. Nobody has forced me to wear it but I feel like I have oppressed and isolated myself.

Maybe I will feel more comfortable among women who dress in a similar fashion, so over 24 hours I visit various parts of London with a large number of Muslims — Edgware Road (known to some Londoners as "Arab Street"), Whitechapel Road (predominantly Bangladeshi) and Southall (Pakistani and Indian). Not one woman is wearing the niqab. I see many with their hair covered, but I can see their faces. Even in these areas I feel a minority within a minority. Even in these areas other Muslims turn and look at me. I head to the Central Mosque in Regent's Park. After three failed attempts to hail a black cab, I decide to walk.

A middle-aged American tourist stops me. "Do you mind if I take a photograph of you?" I think for a second. I suppose in strict terms I should say no but she is about the first person who has smiled at me all day, so I oblige. She fires questions at me. "Could I try it on?" No. "Is it uncomfortable?" Yes. "Do you sleep in it?" No. Then she says: "Oh, you must be very, very religious." I'm not sure how to respond to that, so I just walk away.

At the mosque, hundreds of women sit on the floor surrounded by samosas, onion bhajis, dates, and Black Forest gateaux, about to break their fast. I look up and down every line of worshippers. I can't believe it — I am the only person wearing the niqab. I ask a Scottish convert next to me why this is.

"It is seen as something quite extreme. There is no real reason why you should wear it. Allah gave us faces and we should not hide our faces. We should celebrate our beauty."

I'm reassured. I think deep down my anxiety about having to wear the niqab, even for a day, was based on guilt — that I am not a true Muslim unless I cover myself from head to toe. But the Koran says: "Allah has given you clothes to cover your shameful parts, and garments pleasing to the eye: but the finest of all these is the robe of piety."

Endurance test

I don't understand the need to wear something as severe as the niqab, but I respect those who bear this endurance test — the staring, the swearing, the discomfort, the loss of identity. I wear my robes to meet a friend in Notting Hill for dinner that night. "It's not you really, is it?" she asks.

No, it's not. I prefer not to wear my religion on my sleeve ... or on my face. —

© Guardian Newspapers Limited 2006

By Zaiba Malik

The Hindu, New Delhi

[Orignally printed in The Guardian, UK]

"I DON'T wear the niqab because I don't think it's necessary," says the woman behind the counter in the Islamic dress shop in east London. "We do sell quite a few of them, though." She shows me how to wear the full veil. I would have thought that one size fits all but it turns out I'm a size 54. I pay my £39 and leave with three pieces of black cloth folded inside a bag.

The next morning I put these three pieces on as I've been shown. First the black robe, or jilbab, which zips up at the front. Then the long rectangular hijab that wraps around my head and is secured with safety pins. Finally the niqab, which is a square of synthetic material with adjustable straps, a slit of about five inches for my eyes and a tiny heart-shaped bit of netting, which I assume is to let some air in.

I look at myself in my full-length mirror. I'm horrified. I have disappeared and somebody I don't recognise is looking back at me. I cannot tell how old she is, how much she weighs, whether she has a kind or a sad face, whether she has long or short hair, whether she has any distinctive facial features at all. I've seen this person in black on the television and in newspapers, in the mountains of Afghanistan and the cities of Saudi Arabia, but she doesn't look right here, in my bedroom in a terraced house in west London. I do what little I can to personalise my appearance. I put on my oversized man's watch and make sure the bottoms of my jeans are visible. I'm so taken aback by how dissociated I feel from my own reflection that it takes me over an hour to pluck up the courage to leave the house.

I've never worn the niqab, the hijab or the jilbab before. Growing up in a Muslim household in Bradford in the 1970s and 1980s, my Islamic dress code consisted of a school uniform worn with trousers underneath. At home I wore the salwar kameez, the long tunic and baggy trousers, and a scarf around my shoulders. My parents only instructed me to cover my hair when I was in the presence of the imam, reading the Koran, or during the call to prayer. Today I see Muslim girls 10, 20 years younger than me shrouding themselves in fabric. They talk about identity, self-assurance, and faith. Am I missing out on something?

On the street it takes just seconds for me to discover that there are different categories of stare. Elderly people stop dead in their tracks and glare; women tend to wait until you have passed and then turn round when they think you can't see; men just look out of the corners of their eyes. And young children — well, they just stare, point, and laugh.

I have coffee with a friend on the high street. She greets my new appearance with laughter and then with honesty. "Even though I can't see your face, I can tell you're nervous. I can hear it in your voice and you keep tugging at the veil."

"Buried in black snow"

The reality is, I'm finding it hard to breathe. There is no real inlet for air and I can feel the heat of every breath I exhale, so my face just gets hotter and hotter. The slit for my eyes keeps slipping down to my nose, so I can barely see a thing. Throughout the day I trip up more times than I care to remember. As for peripheral vision, it's as if I'm stuck in a car buried in black snow. I can't fathom a way to drink my cappuccino and when I become aware that everybody in the coffee shop is wondering the same thing, I give up and just gaze at it.

At the supermarket, a baby no more than two years old takes one look at me and bursts into tears. I move towards him. "It's OK," I murmur. "I'm not a monster. I'm a real person." I show him the only part of me that is visible — my hands — but it's too late. His mother has whisked him away. I don't blame her. Every time I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirrored refrigerators, I scare myself.

For a ridiculous few moments I stand there practising a happy and approachable look using just my eyes. But I'm stuck looking aloof and inhospitable, and am not surprised that my day lacks the civilities I normally receive, the hellos, thank-yous and goodbyes.

After a few hours I get used to the gawping and the sniggering, am unsurprised when passengers on a bus prefer to stand up rather than sit next to me. What does surprise me is what happens when I get off the bus. I've arranged to meet a friend at the National Portrait Gallery. In the 15-minute walk from the bus stop to the gallery, two things happen. A man in his 30s, who I think might be Dutch, stops in front of me and asks: "Can I see your face?"

"Why do you want to see my face?"

"Because I want to see if you are pretty. Are you pretty?"

Before I can reply, he walks away and shouts: "You tease!"

Then I hear the loud and impatient beeping of a horn. A middle-aged man is leering at me from behind the wheel of a white van. "Watch where you're going, you stupid Paki!" he screams. This time I'm a bit faster.

"How do you know I'm Pakistani?" I shout. He responds by driving so close that when he yells, "Terrorist!" I can feel his breath on my veil.

Things don't get much better at the National Portrait Gallery. I suppose I was half expecting the cultured crowd to be too polite to stare. But I might as well be one of the exhibits. As I float from room to room, like some apparition, I ask myself if wearing orthodox garments forces me to adopt more orthodox views. I look at paintings of Queen Anne and Mary II. They are in extravagant ermines and taffetas and their ample bosoms are on display. I look at David Hockney's famous painting of Celia Birtwell, who is modestly dressed from head to toe. And all I can think is that if all women wore the niqab how sad and strange this place would be. I cannot even bear to look at my own shadow. Vain as it may sound, I miss seeing my own face, my own shape. I miss myself. Yet at the same time I feel completely naked.

The women I have met who have taken to wearing the niqab tell me that it gives them confidence. I find that it saps mine. Nobody has forced me to wear it but I feel like I have oppressed and isolated myself.

Maybe I will feel more comfortable among women who dress in a similar fashion, so over 24 hours I visit various parts of London with a large number of Muslims — Edgware Road (known to some Londoners as "Arab Street"), Whitechapel Road (predominantly Bangladeshi) and Southall (Pakistani and Indian). Not one woman is wearing the niqab. I see many with their hair covered, but I can see their faces. Even in these areas I feel a minority within a minority. Even in these areas other Muslims turn and look at me. I head to the Central Mosque in Regent's Park. After three failed attempts to hail a black cab, I decide to walk.

A middle-aged American tourist stops me. "Do you mind if I take a photograph of you?" I think for a second. I suppose in strict terms I should say no but she is about the first person who has smiled at me all day, so I oblige. She fires questions at me. "Could I try it on?" No. "Is it uncomfortable?" Yes. "Do you sleep in it?" No. Then she says: "Oh, you must be very, very religious." I'm not sure how to respond to that, so I just walk away.

At the mosque, hundreds of women sit on the floor surrounded by samosas, onion bhajis, dates, and Black Forest gateaux, about to break their fast. I look up and down every line of worshippers. I can't believe it — I am the only person wearing the niqab. I ask a Scottish convert next to me why this is.

"It is seen as something quite extreme. There is no real reason why you should wear it. Allah gave us faces and we should not hide our faces. We should celebrate our beauty."

I'm reassured. I think deep down my anxiety about having to wear the niqab, even for a day, was based on guilt — that I am not a true Muslim unless I cover myself from head to toe. But the Koran says: "Allah has given you clothes to cover your shameful parts, and garments pleasing to the eye: but the finest of all these is the robe of piety."

Endurance test

I don't understand the need to wear something as severe as the niqab, but I respect those who bear this endurance test — the staring, the swearing, the discomfort, the loss of identity. I wear my robes to meet a friend in Notting Hill for dinner that night. "It's not you really, is it?" she asks.

No, it's not. I prefer not to wear my religion on my sleeve ... or on my face. —

© Guardian Newspapers Limited 2006

2 comments:

Dear whoso ever posted this article here.

Here are my comments:

1. You have the liberty to wear niqab, its upto u. After all you will be responsible for your deeds and yourself would be answerable to the lord of this Universe, on the Judgement day.

2. Practically speaking, a muslim man should lower his gaze and not look at un-related woman, but what if he doesnt do, and what if you dont cover ur face. Face is part of the womens beauty. And your face will attract opposite sex, its natural. He may develop haram feelings in his mind, looking at ur face. It is normal, quite human. So do u want to be part of this whole sequence where u are involved in a bad deed of your fellow muslim brother, if yes, then it is upto u.

3. And read Quran 24:31.

Regards

Dear Mr. Anonymous,

Has it ever occured to you that women are humans, not objects of your 'haraam desires' which btw, is not just reserved for women, but there are cases when other men and minors too have been ogled at quite mischieviously. Does it mean everyone should start covering their faces to avoid haramful stares?

That's completely absurd.

Post a Comment