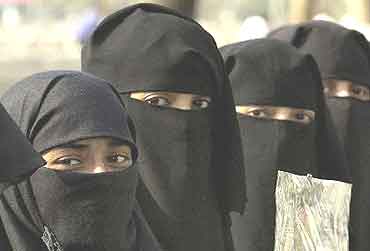

Wearing the Muslim veil conveys exclusion

Oh, this is rich: a defence of the veil as feminist prerogative. What next — promotion of the chastity belt as post-feminist birth control?

Events thousands of miles away, in England, are resonating here in Canada, in yet another round of politicized and polarizing debate over the alleged "otherness" of pious Muslims, the purported unwillingness of some to accept the secular status quo of the Western societies in which they reside.

In this case, a young teaching assistant's refusal to remove her niqab — the piece of cloth that some Muslim women wear to cover their faces, hiding everything below the eyes — has triggered anew fierce suspicions of multiculturalism accommodation run amok, demonstrating again how damnably difficult it has become to separate isolated cases from the larger context of political and ideological agendas.

What some frame as a religious obligation or simply esthetic choice has been taken up by others as evidence of bigotry, on one side, and self-imposed segregation on the other, an in-your-face rejection of values held most dear by the dominant culture.

One value: We are our faces.

Individuals — not just part of various collectives as defined by gender or faith, but each of us distinguishable by features that express what's going on inside.

Identities — the openness of a society that's revealed in every single countenance, reinforcing the central fact of diversity and pluralism, our shared humanity.

In Western societies, indeed in most Islamic societies, too, we relate to one another at least initially by what we can see: the smile, the frown, what's crossing our minds crossing our faces, too. The niqab, whatever its other messages may be, says: You can't see and you must not see.

What I have under here is so sacred, so untouchable, that just your glance is contaminating. You are not to be entrusted with the privilege of knowing me even so much as this.

What I have under here is so sacred, so untouchable, that just your glance is contaminating. You are not to be entrusted with the privilege of knowing me even so much as this.

I can think of no more insulating a statement than the veil. That one small rectangle of fabric speaks volumes about separateness and exclusion. It carries both an intrinsic sense of superiority (my faith, which sets me apart) and inferiority (my gender, which renders me de facto prey, thus requiring this protection, which just happens to be the invention of males).

Humbleness versus arrogance.

From this hard knot of contradictions has unravelled a further thread, a substrata string, and the most preposterous rationalization of all, particularly coming out of the mouths of men — that the niqab is a feminist declaration. This is so duplicitous a construct as to be almost comical, if it weren't being seriously posed in some quarters, and helpfully parroted by a small number of women who apparently have no confidence in either their own character or the ability of the opposite sex to control their beastly tendencies.

Really, we can be our own worst enemies sometimes. And, more unforgivably, the enemy of other women.

There are, perhaps, legitimate reasons for asserting a woman's right not to show anything other than her eyes to the world, and barely that. In a free country, one would like to believe that women — including Muslim women, in conservative communities — are making independent choices, based on their own needs and wishes and comfort zone.

But let's not be disingenuous here. There is ample evidence, overwhelming evidence, of religious and cultural pressures, those steeped in a firmly patriarchal code of conduct, for the marginalizing of adult females, practices that are fundamentally at odds with basic concepts of gender equality.

Ontario came alarmingly close to permitting the application of sharia law in family arbitration matters — when multicultural sensitivities almost trumped women's rights — before Premier Dalton McGuinty stepped in and said "no," that's just not acceptable, however cloaked in the disguise of ethnic and ethic reasoning.

Sharia law works, is made to work, by coercive imposition in Islamist countries where women are chattels, and largely illegitimate governments rely on the support of religious authorities for even the slimmest of mutually satisfying endorsement.

Sharia law works, is made to work, by coercive imposition in Islamist countries where women are chattels, and largely illegitimate governments rely on the support of religious authorities for even the slimmest of mutually satisfying endorsement.

In some Islamic jurisdictions — just as an example — rape cases can only pass the trial test if four people come forward as witnesses to the crime. How often do you think that occurs?

What was most disheartening to many of us about the barely averted sharia threat here is that the proposal had been studied and advanced by a woman, no less than the province's previous attorney general, in an NDP government.

This provided threadbare cover, deeply dishonest on its merits, for an alliance of reactionaries and fundamentalists (whether born-again or always-were) to justify treating Muslim women as lesser beings. Sharia law would have exposed a palpably vulnerable constituency to the paternalistic mercies of religious tribunals.

This provided threadbare cover, deeply dishonest on its merits, for an alliance of reactionaries and fundamentalists (whether born-again or always-were) to justify treating Muslim women as lesser beings. Sharia law would have exposed a palpably vulnerable constituency to the paternalistic mercies of religious tribunals.

I do not trust the sophistry inherent in a pedantically twisted intellectualization of the veil, as if it were something other than what it demonstrably is: segregation of women by other means.

We have long progressed beyond the point where the Bible could be used to justify misogyny.

No sane person would quote from Scripture — or be permitted to do so, in a mass-market general newspaper — those anachronistic texts that sanction unequal treatment of women up to and including the beating of a disobedient spouse or child. Bible-thumping is repellent, whether applied to women or children or homosexuals or any other group whose behaviour is construed as sinful.

No sane person would quote from Scripture — or be permitted to do so, in a mass-market general newspaper — those anachronistic texts that sanction unequal treatment of women up to and including the beating of a disobedient spouse or child. Bible-thumping is repellent, whether applied to women or children or homosexuals or any other group whose behaviour is construed as sinful.

Qu'ran-thumping should be no less unsavoury.

So spare me what that holy book has to say about veiling women, especially when even Islamic scholars are divided on it. Like Britain, ours is a secular society trying to cope with conflicting demands; we protect the rights of people to be religious, as they see fit, and not religious, as they see fit. What we've not done a very good job of is protecting the dignity, sometimes the very lives, of wives and daughters and sisters who are very much under the thumb of fathers, husbands and brothers, viewed as property, a reflection on their own paramount authority in the household.

It is not patronizing to acknowledge that many Muslim women who wear the niqab — and they are themselves in a small minority — do so not out of personal choice but because they are bullied, tacitly or overtly, into doing so. They must hide their faces so that their men don't lose face.

And I care a great deal more about their predicament than I do their Islamist sisters who choose to veil under the rubric of feminism.

No comments:

Post a Comment