November 04, 2006

Pakistani Judge tells veil wearing lawyer to take it off

Friends,

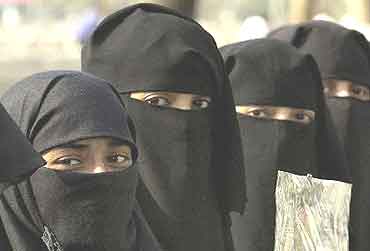

In Pakistan's North West Frontier Province, a coalition of Islamist political parties governs the province. In the provincial legislature, a dozen or more women MPs sit in a cluster, covered from head to toe in black burkas, making the speaker's job almost impossible.

No one knows who is behind the burqas as it is not permitted to check the identities of these MPs. Imagine this in the House of Commons in Ottawa or the US Senate. Imagine the speaker not being able to know who said what or whether the person sitting in Belinda Stronach's chair is Belinda herself or Peter McKay!

The problem of the burka is compounded in the courts, where some lawyers are appearing in veils and the judges cannot see who they are talking to. This came to a head yesterday when the Chief Justice of the Peshawar High Court ordered a woman lawyer to take off her niqaab so he could see her and hear her. Here is a report of this incident from the Pakistani newspaper, The Times.

Read and reflect.

Tarek

------------ --------- --------- -----

Saturday, November 04, 2006

Pakistan Chief Justice

says no to veiled lawyers

By Akhtar Amin

Daily Times, Pakistan

PESHAWAR, Pakistan - Peshawar High Court (PHC) Chief Justice Tariq Pervaiz Khan has ordered women lawyers not to wear veils in courtrooms, saying they (the women lawyers) could neither be identified nor assist the court well in veils. “You (women lawyers) are professionals.

You should be dressed as requisite for the lawyers. We (the judges) cannot identify women lawyers wearing veils and doubt that veiled lawyers appear in court several times seeking adjournments for other lawyers’ cases,” Justice Pervaiz told a veiled lawyer, Raees Anjum, who was seeking adjournment of a case.

The court could barely hear Ms Anjum’s name when she was asked to make her presence for a case she was seeking an adjournment for. Ms Anjum had to repeat her name several times because of her veil and this led to the chief justice’s observation that women lawyers should not wear veils in courtrooms.

“I was embarrassed when the chief justice asked me not to wear a veil in the courtroom,” Ms Anjum told Daily Times. “I feel more confident in my hijab (veil). I am a progressive Muslim woman who has the courage to follow her faith while living and working in this conservative society.... hijab reflects a woman’s modesty,” she said.

She added that several women judges in the NWFP (Pakistan's province bordering Afghanistan) wear a veil and all MMA (Islamist allaince ruling the province) women MPs are also veiled. Ms Anjum told Daily Times that there was a difference of opinion in the judiciary on the issue.

“On one hand, Peshawar Sessions Judge Hayat Ali Shah tells women lawyers to wear veils when coming to his court, while the PHC chief justice wants women lawyers appearing in court without veils.”

November 02, 2006

German Muslim MP urges her sisters: "Wake up to today's Germany. This is where you live, so take off your veils"

November 2, 2006

November 2, 2006 German Politicians Rally around Muslim Lawmaker in Headscarf Row

Politicians from across the spectrum have expressed solidarity with a Green Party parliamentarian of Turkish origin who has received death threats after urging Muslim women in Germany to take off their headscarves.

Elkin Deligöz' comments in a newspaper article two weeks ago sparked not just a deluge of criticism by religious leaders and the media in Turkey but also intimidation. The Green Party parliamentarian has received death threats and is now under police protection.

The incident has, although somewhat belatedly, led to a slew of German politicians -- ranging from her fellow left-wing party members to lawmakers from the center-right -- to express their support and defend her right to speak her mind.

Freedom of expression must be protected, said German Interior Minister Wolfgang Schäuble. "It's not OK when someone is threatened" for exercising that right. He called on politicians to do everything they could to throw their weight behind Deligöz.

The Green Party's co-leader in parliament, Renate Künast, has already complained to Turkey's ambassador in Berlin of "unacceptable" reactions in Turkish media to Deligöz' comments.

Newspapers in Turkey had called Deligöz a "Turkish Nazi" and a "disgrace to mankind."

Meeting with Islamic groups

Künast invited several Islamic organizations for discussions on Tuesday, including the Islamic Council, the Turkish Association of Berlin and Brandenburg and the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs. Several representatives stressed that they did not agree with Deligöz' opinion, but condemned the threats she had received.

"What she said is nonsense to me," said chairman of the Turkish Community in Germany, Kenan Kolat. But he added that it was important that "she is allowed to spread this nonsense."

Deligöz, who was born in Turkey but grew up in Germany, addressed Muslim women living in Germany in a newspaper article recently, saying: "Wake up to today's Germany. This is where you live, so take off your veils."

After the meeting on Tuesday, Deligöz stressed that she would not allow herself to be intimidated, and that she stood by her opinion on headscarves in Germany.

"I am going to live my life from now on just as I have up to now," she said. "I stand by my comments and I have no reason to deviate from them whatsoever."

Integration of Germany's Muslim population has been a hot-button issue in Germany for some time. It has become a priority for Chancellor Angela Merkel's government as concern grows about Islamic radicalisation across Europe and the emergence of an underclass of disillusioned young Muslims in the country, who are mostly Turks.

Recent moves by a theater in Berlin to cancel a opera that featured the severing of the heads of religious figures, including that of Prophet Mohammed, for fear of Islamist attacks was strongly condemned by politicians. Though the opera has since been reinstated, the incident has served to underline the growing debate on freedom of speech in Europe and whether it should have limits when it comes to offending religious sensibilities.

Support from the right

Wolfgang Bosbach, deputy head of the conservative Christian Democratic parliamentary group, called on Germany and its leaders to "show some backbone."

"She (Deligöz) has earned the unconditional support of all of civilized society," he told the broadcaster n-tv.

November 01, 2006

India's leading Muslim cleric, the Imam of New Delhi's Jama Mosque, describes Shabana Azmi as a Prostitute

November 1, 2006

November 1, 2006The Shabana Azmi Controversy:

Leading Indian Imam refers to her as the 'Naachne Gaane Waali Aurat'

Outlook India

So what's the song and dance all about? Why is that instead of being felicitated for the honour bestowed on her, Shabana Azmi finds herself in the middle of a controversy? What did she really say about the veil? And what are her critics going on about?

It was a moment of glory for Shabana Azmi as she became the first Indian recipient of the prestigious International Gandhi Peace Prize, after such luminaries in the past as the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

"I am truly overwhelmed and humbled to receive the covetous award. My joy on this occasion has been doubled because Vanessa Redgrave, who has been my hero for many years, both as an actress of immeasurable talent and a woman of tremendous courage who has stuck her neck out of for her political convictions and issues of human rights and social justice, has consented to give me the Award," she had said in her acceptance speech at the House of Commons in London.

"Terrorism is being equated with Islam," she had pointed out: "This is both unjust and untrue. Myths are being perpetuated in the name of religion. Islam resides in more than 50 countries in the world and takes on the culture of the country in which it resides. So it is tolerant in some, liberal in some, extremist in others".

"The fight today cannot be between the Christian and the Muslim, the fight cannot be between the Hindu and the Muslim—the fight needs to be between ideologies—the ideologies of the liberal versus the ideologies of the extremist. The liberal Muslim, Christian, Hindu on the same side against the extremist Muslim, Christian, Hindu on the other," Azmi said in her Gandhi Memorial Lecture 'Non-Violence Is Possible'.

She also spoke on the condition of women in India: "It is true that in India, women on one hand are moving from strength to strength, on the other we also have to confront the horrific violence of female foeticide. It is ironic that a country that worships its women as goddesses also devalues its girl child - denies her access to equal opportunity and is even denying her the right to life. We must put an end to this violence now."

But that was not all. She was confronted with a question on the current veil controversy raging in Britain, and her answer was very simple:

"The Quran speaks about women wearing clothes to cover her modesty. A woman is supposed to cover herself to be modest. She does not need to cover her face. A time has come for a debate on the issue"

Later, in India, when asked to clarify what exactly her views were, she said that while she thinks that the Koran does not explicitly ask women to cover their faces, and they should not be forced to do so as it prevents social interaction and hampers communication, and that Muslims too need to evolve with the times and adapt given the context and situation.

She stressed that for many people, wearing the veil could even be a way of protest against the British policies post-9/11 and that many may just want to make a point of asserting their distinct religious identity. She also took pains to point out that for her issue was that a compulsion of any kind should not be allowed, that no one should be compelled to wear or not wear a veil, and that in addition remarks such as Jack Straw's would make even her to want to cover her face not under one but three veils, just to register her protest.

But she once again reiterated that the time has come for Muslims to debate the issue seriously. Instead of a debate, what followed were usual personal attacks. The first to lead the charge was the Shahi Imam of Jama Masjid, New Delhi, and others including the general secretary of the highly influential Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind followed suit. Prominent Shia clerics and well-known liberals such as Arif Mohammed Khan and Syeda Hameed have spoken out in her favour. A sampling of some of the soundbytes:

Syed Ahmed Bukhari, Imam, Jama Masjid, New Delhi: "Who has authorized Shabana Azmi to interpret the Quran? She is not a Muslim, she is just a 'naachne gaane waali aurat' — a woman who sings and dances — and she should confine herself to her profession and must not speak on things she has no knowledge about. She does not represent the mainstream views within the community. If there is no controversy on Christian nuns wearing a habit, so why should people look for controversy over a Muslim woman wearing a veil? The Quran clearly instructs Muslim women to wear a veil, though it is always up to the followers of any religion how sincerely they follow its principles. Many of our Muslim brethren do take alcohol. But this conduct of theirs does not refute the fact that taking any type of intoxicant is forbidden in Islam. If a woman chooses to move out without a burqa, it would be considered against the tenets of Islam."

Kalbe Sadiq, All India Muslim Personal Law Board: "The Quran only says that the head of a woman and a bit of her face should be covered. There is no need to cover the whole face. There is no mention of the "Talbani purdah" in the Koran. Islam is against the head-to-toe coverings imposed by the Taliban in Afghanistan. The Surah Noor from the Quran demands of a man not to look at the face of a woman and asks him to lower his gaze to protect her modesty."

Khalid Rasheed, Firangimahali, All India Muslim Personal Law Board: "It has become a fashion for some Indian Muslims to criticize the teachings of the holy Quran."

Maulana Mahmood Madani, Rajya Sabha member and general secretary, Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind: "Only Islamic scholars can speak on such issues, Azmi has received no Islamic education, it's only proper for Muslim women to wear veil, what she has said is an offence against Islam. She is talking about a sensitive issue without authority."

Arif Mohammad Khan, former Union minister, BJP: "Islam is against compelling mankind against their will. Islam is against imposition of norms and attitudes. It only expects men and women to dress decently and not to provoke lewdness."

Syeda Hameed, member, Planning Commission: "The modesty code in Islam applies equally to men and women. Islam does not compel women to cover their faces, They are unnecessarily raising a controversy. The clamour against Shabana is an _expression of male bias. Nobody bothers about the Koranic injunctions on how to dress for men. It's ridiculous, women should speak out."

Liberals find much merit in Syeda Hameed's argument that despite there being explicit injunctions on the male way of dressing too, no one seems to be interested in enforcing any dress-code on such well-known Muslim men as any of the Mumbai film industry Khans or sportsmen, but Tennis star Sania Mirza's sporting gear was picked on, just as Shabana Azmi's call for a debate has been sensationalised. It is clear, they point out, that the patriarchal clergy is fighting a desperate battle against modernity's evolutionary onslaught.

In India, so far, any sort of a compulsion has always been frowned upon, even in Kashmir, as Dukhtaran-e-Millat had found out when it tried to enforce a compulsory Talibanesque purdah on the women in the valley. There were not many takers, despite threats of serious bodily harm. Elsewhere in India too, it has been well-established that the veil has more to do with cultural or regional, and less with religious, dimensions.

The traditional ghungat among the Hindu women in Rajasthan and elsewhere, or the non-observance of purdah by many Muslim women, which hardly ever elicits a comment, makes this abundantly clear.

But with Shabana Azmi's intervention, it is clear that the debate over the compulsory veil for the Muslim women has come out of the purdah.

October 31, 2006

Mona Eltahawy says, "Women are not candy"

October 24, 2006

"The niqab, or the face veil, terrifies me"

Faith dressed in tribal garb as Muslims debate British ruling on niqab

By Mona Eltahawy

The niqab, or the face veil, terrifies me. I am a Muslim woman for whom the niqab says very little about religion but a whole lot about the erasure of a woman's identity, her very existence as a human being in any society.

I am the first to admit that my views on the niqab are thoroughly grounded as much in my own very personal struggles with the Hijab, which I wore for nine years, as they are more generally with the obsessive focus on how Muslim women dress - an obsession shared by Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

An argument I had years ago - while I still wore Hijab - on the Cairo subway with a woman who wore niqab helped seal for good my refusal to defend the niqab. The woman, dressed in black from head to toe, began by asking me why I did not wear the niqab. I pointed to my headscarf and asked her "Is this not enough?"

I will never forget her answer.

"If you wanted a piece of candy, would you choose an unwrapped piece or one that came in a wrapper?" she asked. "I am not candy," I answered. "Women are not candy."

I have since heard arguments made for the niqab in which the woman is portrayed as a diamond ring or a precious stone and other such objects that need to be hidden as a way of proving their "worth".

And so to this day I unequivocally refuse to defend the niqab, regardless of who is making the argument for or against it. That is especially true in the wake of British House of Commons leader Jack Straw's comments that the niqab prevents communication. He is absolutely right. It prevents a reading of the face and its expressions, vital ingredients in human communication.

While some have grasped Straw's comment as but the latest onslaught against Muslims, others have wisely tried to make the most of the door that Straw kicked down by daring to broach the subject. Just because some British Muslim women wear niqab, it does not become incumbent on every Muslim everywhere to defend the niqab, over which there is no Muslim consensus.

Witness a parallel controversy that erupted in Egypt soon after Straw ignited his firestorm. The dean of Helwan University, south of Cairo, issued an ultimatum warning students they would not be able to stay at college dorms unless they removed their niqab. The dean based his decision on security grounds, saying that men disguised as women in niqab could slip into the female dorms.

In the midst of Egypt's niqab controversy, Soad Saleh, a professor of Islamic law and former dean of the women's faculty of Islamic studies at Al-Azhar University, Egypt, said that the face covering had nothing to do with Islam.

"I don't agree that the veil should be compulsory, and I don't like it," Saleh told Agence France Press. She said she wants to "purge Islam of false concepts: the Quran does not say women have to cover their faces, it's an old Bedouin tradition."

Amnah Nousir, a professor of Islamic philosophy, told the Dubai-based Gulf News that "The niqab was common in the Arabian Peninsula centuries before Islam and was not imposed by this religion."

"The face is one's mirror. So why should the woman hide herself behind this black veil?" she told Gulf News. Gamal el-Banna, a liberal Muslim thinker, said recently "the niqab is an insult and he who calls for it is backward".

It is important to hear Muslim women and men take a stand against the niqab so that it doesn't join the ever growing list of identity politics issues that is waved in the face of Muslims everywhere as a sort of litmus test. If we don't check our agreement to every box on the list, we are somehow less authentic or less Muslim.

Such a list is both dangerous and disingenuous because those writing its contents are usually the most conservative in the Muslim community.

If we are not offended by the Danish cartoons of Prophet Mohammed , if we are not enraged at the Pope's comments on Islam and violence, if we are not up in arms over Jack Straw's niqab statement then we're portrayed as at best Muslims who don't care enough or at worst sell-outs and self-hating Muslims. And it is even worse when non-Muslims make such accusations which at their core basically imply that they acknowledge only one kind of Muslim.

That the niqab is even an issue in the U.K. or Europe is quite astounding for this Egyptian Muslim woman who grew up with stories about feminist leader Hoda Sharawi who, upon returning to Egypt from a women's conference in Rome in 1923, famously removed her face veil on a Cairo train station platform.

To see a woman wearing niqab on the streets of Copenhagen as I did just a few weeks ago and to read about the case of the British Muslim teacher Aisha Azmi who insists that her face veil does not hinder her ability to teach is to shudder at how little progress has been made in the more than 90 years since Sharawi so bravely broke with her country's tradition at the time and refused to cover her face anymore.

That more than 90 years later the niqab is still with us and has migrated to the West is a sad indictment of how far the issue of Muslim women's rights has regressed and an even sadder reminder of how Muslim women's bodies have become just another battlefield for those determined to slug out the clash of civilizations.

Azmi was recently awarded £1,000 for being victimized by officials who told her to remove her full-face veil while teaching. But her more serious claims - of religious discrimination and harassment - were rejected by an employment tribunal.

It is incredible that her case came to this. Azmi taught 11-year-olds learning English as a second language. The school suspended her in November 2005 after she refused to remove her veil at work, telling her that students found it hard to understand her during lessons and that face-to-face communication was essential for her job. And of course the school was right on both counts.

That was exactly Straw's point and that was why he said he would ask women who wore niqab to remove it before they met with him in his office. Azmi said she was willing to remove her veil in front of children or other female teachers, but not in front of men. But as Reuters reported, she insisted at a news conference that "the veil doesn't cause a barrier" between teacher and student.

In early 20th century Egypt, delegations were sent to Europe to learn and bring home to Egypt the modern intellectual tools the country needed to industrialize and develop. The West, back then, was not the enemy.

And so it is sadly ironic that Islamists are now engaged in a reverse kind of export by bringing to the West ideas and practices that are vigorously challenged in the East as both Soad Saleh and Gamal el-Banna have shown above.

For those of us who criss-cross the West and East, our best line of defence against Islamist thinking is to offer our personal experiences with niqab, hijab and other issues that Muslims are assumed and expected to agree on.

I first put on the hijab at the age of 16, a year after my family moved from the UK to Saudi Arabia. I chose to wear it, thinking that I was fulfilling a religious obligation required of Muslim women. But in reading the work of various Muslim scholars, particularly female writers such as the Moroccan sociologist Fatima Mernissi and Egyptian-American Harvard University scholar Leila Ahmed, I learned that the verses in the Quran that are most often used to call for the hijab have been interpreted differently.

I have also learned to stop arguing about the hijab. It is a waste of time and energy and distracts from the much greater issues that most Muslim women are concerned with, particularly in the developing world where poverty, illiteracy and the near impossibility of filing for divorce are often much higher on the list of worries.

My rejection of the niqab however remains absolute, regardless of geography. My years in Saudi Arabia taught me that niqab in that country is a marriage of Saudi Arabia's particular interpretation of Islam and its tribal traditions.

The niqab has no place in mainstream Muslim thought. As Muslims in the West we must resist joining those Islamists who insist on giving it a place in European capitals where hard-won women's rights took decades to establish and enshrine. We must not allow Islamists to so easily erase Muslim women out of existence.

October 26, 2006

Rosie DiManno question's the wearing of the Niqab as 'feminism'

Wearing the Muslim veil conveys exclusion

By Rosie DiManno

What I have under here is so sacred, so untouchable, that just your glance is contaminating. You are not to be entrusted with the privilege of knowing me even so much as this.

Sharia law works, is made to work, by coercive imposition in Islamist countries where women are chattels, and largely illegitimate governments rely on the support of religious authorities for even the slimmest of mutually satisfying endorsement.

This provided threadbare cover, deeply dishonest on its merits, for an alliance of reactionaries and fundamentalists (whether born-again or always-were) to justify treating Muslim women as lesser beings. Sharia law would have exposed a palpably vulnerable constituency to the paternalistic mercies of religious tribunals.

No sane person would quote from Scripture — or be permitted to do so, in a mass-market general newspaper — those anachronistic texts that sanction unequal treatment of women up to and including the beating of a disobedient spouse or child. Bible-thumping is repellent, whether applied to women or children or homosexuals or any other group whose behaviour is construed as sinful.

Sweden's Muslim minister turns on veil: Nyamko Sabuni wants to ban the Hijab on children

October 22, 2006

October 22, 2006Sweden's Muslim

minister turns on veil

By Helena Frith Powell

The Sunday Times, London

THE latest media darling of Scandinavian politics is not only black, beautiful and Muslim; she is also firmly against the wearing of the veil.

Nyamko Sabuni, 37, has caused a storm as Sweden’s new integration and equality minister by arguing that all girls should be checked for evidence of female circumcision; arranged marriages should be criminalised; religious schools should receive no state funding; and immigrants should learn Swedish and find a job.

Supporters of the centre-right government that came to power last month believe that her bold rejection of cultural diversity may make her a force for change across Europe. Her critics are calling her a hardliner and even an Islamophobe.

“I am neither,” she said in an interview. “My aim is to integrate immigrants. One is to ensure they grow up just as any other child in Sweden would.”

Sabuni believes all immigrants must try to become proficient in Swedish — just as she did when she arrived from Africa aged 12 — rather than alienating locals.

“Language and jobs are the two most crucial things for integration,” she said. “If you want to become a Swedish citizen, we think you should have some basic knowledge of Swedish.”

An elegant, vivacious woman who uses subtle make-up and wears soft clothes in pastel shades and tight woollen sweaters, she argues for a total ban on veils being worn by girls under the age of consent, which is 15 in Sweden.

“Nowhere in the Koran does it state that a child should wear a veil; it stops them being children. By putting a veil on a girl you are immediately saying to the outside world that she is sexually mature and has to be covered. It’s wrong,” she said.

Sabuni was born in Burundi. Her father was a political dissident who was in prison during much of her early childhood. In 1980 he was granted asylum in Sweden. The next year his wife and six children joined him and they settled near Stockholm.

Sabuni read law at Uppsala University, Sweden’s equivalent of Oxbridge, and became a public relations consultant. Her husband, who works in the travel industry and runs their home in Stockholm, took paternity leave when their twin boys, now five, were born.

In Sweden she is best known for her suggestion that adolescent girls should have compulsory examinations to make sure they have not been subjected to genital mutilation. “It would enable us to prosecute people carrying out the practice,” she said.

According to Sabuni, many politicians have shied away from talking about the need for assimilation rather than multi-culturalism: “I am one of the few who dares to speak out. Sadly, some members of the Muslim community feel picked on.”

Muslim groups in Sweden are already organising a petition to have her removed from government. “I regret that Muslims feel I am a threat to them,” she said. “Everybody has a right to practise their religion, but I will never accept religious oppression. And I represent the whole of society, not just the Muslims.”

Despite her ascendancy in her adopted country, Sabuni says that Sweden, where immigrants — half of them Muslims — make up nearly 12% of the population, has been only moderately successful at integration: “We have a whole underclass of people who don’t have jobs, who don’t speak the language and who are living on the fringes of society.”

Although fighting discrimination is one of her stated aims, she effectively closed down a Centre Against Racism last week by withdrawing its £400,000 state funding. By chance, the centre was run by her uncle.

“It didn’t achieve its aims,” she said bluntly. “It simply didn’t do what it set out to do, so I had to pull the plug. My uncle is a good and a competent man, but a whole institute can’t be run by one man. He understands that I have to do my job.”

Other ministers appointed by Fredrik Reinfeldt, the prime minister, are more concerned about their jobs. Since he took over on September 17, two ministers have resigned in a series of minor scandals involving unpaid television licences and black-market domestic help, and two more are under pressure to go.

Should Reinfeldt’s government fall, Sabuni would be willing to step into his shoes. On a TV show three years ago she declared that she would become Sweden’s first female prime minister. “I stand by that,” she said. “It’s not something I think about on a daily basis but, if I’m in politics, the ultimate aim has to be to become prime minister.”

Anders Jonsson, a political commentator on the liberal newspaper Expressen, says there is no doubt Sabuni is one to watch. “She is a tough cookie and incredibly ambitious,” he said. “But I think it’s good that a black woman is raising these issues and she has proved that she is prepared to take tough decisions in order to get things done.”

October 25, 2006

Baby bursts in tears on seeing woman in Niqaab

Friends,

Friends,British Muslim journalist Zaiba Malik had never worn the niqab. But with everyone from Jack Straw to Tessa Jowell weighing in with their views on the veil, she decided to put one on for the day. She was shocked by how it made her feel — and how strongly strangers reacted to it.

Here is her story. She recounts being at a mosque and finding out that she was the only one in the face mask,

"At the mosque, hundreds of women sit on the floor surrounded by samosas, onion bhajis, dates, and Black Forest gateaux, about to break their fast. I look up and down every line of worshippers. I can't believe it — I am the only person wearing the niqab. I ask a Scottish convert next to me why this is. "It is seen as something quite extreme. There is no real reason why you should wear it. Allah gave us faces and we should not hide our faces. We should celebrate our beauty."

Zaiba Malik then writes about her encounter with a baby:

"At the supermarket, a baby no more than two years old takes one look at me and bursts into tears. I move towards him. "It's OK," I murmur. "I'm not a monster. I'm a real person." I show him the only part of me that is visible — my hands — but it's too late. His mother has whisked him away. I don't blame her. Every time I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirrored refrigerators, I scare myself."

Read and reflect.

Tarek

----------------------

October 25, 2006

By Zaiba Malik

The Hindu, New Delhi

[Orignally printed in The Guardian, UK]

"I DON'T wear the niqab because I don't think it's necessary," says the woman behind the counter in the Islamic dress shop in east London. "We do sell quite a few of them, though." She shows me how to wear the full veil. I would have thought that one size fits all but it turns out I'm a size 54. I pay my £39 and leave with three pieces of black cloth folded inside a bag.

The next morning I put these three pieces on as I've been shown. First the black robe, or jilbab, which zips up at the front. Then the long rectangular hijab that wraps around my head and is secured with safety pins. Finally the niqab, which is a square of synthetic material with adjustable straps, a slit of about five inches for my eyes and a tiny heart-shaped bit of netting, which I assume is to let some air in.

I look at myself in my full-length mirror. I'm horrified. I have disappeared and somebody I don't recognise is looking back at me. I cannot tell how old she is, how much she weighs, whether she has a kind or a sad face, whether she has long or short hair, whether she has any distinctive facial features at all. I've seen this person in black on the television and in newspapers, in the mountains of Afghanistan and the cities of Saudi Arabia, but she doesn't look right here, in my bedroom in a terraced house in west London. I do what little I can to personalise my appearance. I put on my oversized man's watch and make sure the bottoms of my jeans are visible. I'm so taken aback by how dissociated I feel from my own reflection that it takes me over an hour to pluck up the courage to leave the house.

I've never worn the niqab, the hijab or the jilbab before. Growing up in a Muslim household in Bradford in the 1970s and 1980s, my Islamic dress code consisted of a school uniform worn with trousers underneath. At home I wore the salwar kameez, the long tunic and baggy trousers, and a scarf around my shoulders. My parents only instructed me to cover my hair when I was in the presence of the imam, reading the Koran, or during the call to prayer. Today I see Muslim girls 10, 20 years younger than me shrouding themselves in fabric. They talk about identity, self-assurance, and faith. Am I missing out on something?

On the street it takes just seconds for me to discover that there are different categories of stare. Elderly people stop dead in their tracks and glare; women tend to wait until you have passed and then turn round when they think you can't see; men just look out of the corners of their eyes. And young children — well, they just stare, point, and laugh.

I have coffee with a friend on the high street. She greets my new appearance with laughter and then with honesty. "Even though I can't see your face, I can tell you're nervous. I can hear it in your voice and you keep tugging at the veil."

"Buried in black snow"

The reality is, I'm finding it hard to breathe. There is no real inlet for air and I can feel the heat of every breath I exhale, so my face just gets hotter and hotter. The slit for my eyes keeps slipping down to my nose, so I can barely see a thing. Throughout the day I trip up more times than I care to remember. As for peripheral vision, it's as if I'm stuck in a car buried in black snow. I can't fathom a way to drink my cappuccino and when I become aware that everybody in the coffee shop is wondering the same thing, I give up and just gaze at it.

At the supermarket, a baby no more than two years old takes one look at me and bursts into tears. I move towards him. "It's OK," I murmur. "I'm not a monster. I'm a real person." I show him the only part of me that is visible — my hands — but it's too late. His mother has whisked him away. I don't blame her. Every time I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirrored refrigerators, I scare myself.

For a ridiculous few moments I stand there practising a happy and approachable look using just my eyes. But I'm stuck looking aloof and inhospitable, and am not surprised that my day lacks the civilities I normally receive, the hellos, thank-yous and goodbyes.

After a few hours I get used to the gawping and the sniggering, am unsurprised when passengers on a bus prefer to stand up rather than sit next to me. What does surprise me is what happens when I get off the bus. I've arranged to meet a friend at the National Portrait Gallery. In the 15-minute walk from the bus stop to the gallery, two things happen. A man in his 30s, who I think might be Dutch, stops in front of me and asks: "Can I see your face?"

"Why do you want to see my face?"

"Because I want to see if you are pretty. Are you pretty?"

Before I can reply, he walks away and shouts: "You tease!"

Then I hear the loud and impatient beeping of a horn. A middle-aged man is leering at me from behind the wheel of a white van. "Watch where you're going, you stupid Paki!" he screams. This time I'm a bit faster.

"How do you know I'm Pakistani?" I shout. He responds by driving so close that when he yells, "Terrorist!" I can feel his breath on my veil.

Things don't get much better at the National Portrait Gallery. I suppose I was half expecting the cultured crowd to be too polite to stare. But I might as well be one of the exhibits. As I float from room to room, like some apparition, I ask myself if wearing orthodox garments forces me to adopt more orthodox views. I look at paintings of Queen Anne and Mary II. They are in extravagant ermines and taffetas and their ample bosoms are on display. I look at David Hockney's famous painting of Celia Birtwell, who is modestly dressed from head to toe. And all I can think is that if all women wore the niqab how sad and strange this place would be. I cannot even bear to look at my own shadow. Vain as it may sound, I miss seeing my own face, my own shape. I miss myself. Yet at the same time I feel completely naked.

The women I have met who have taken to wearing the niqab tell me that it gives them confidence. I find that it saps mine. Nobody has forced me to wear it but I feel like I have oppressed and isolated myself.

Maybe I will feel more comfortable among women who dress in a similar fashion, so over 24 hours I visit various parts of London with a large number of Muslims — Edgware Road (known to some Londoners as "Arab Street"), Whitechapel Road (predominantly Bangladeshi) and Southall (Pakistani and Indian). Not one woman is wearing the niqab. I see many with their hair covered, but I can see their faces. Even in these areas I feel a minority within a minority. Even in these areas other Muslims turn and look at me. I head to the Central Mosque in Regent's Park. After three failed attempts to hail a black cab, I decide to walk.

A middle-aged American tourist stops me. "Do you mind if I take a photograph of you?" I think for a second. I suppose in strict terms I should say no but she is about the first person who has smiled at me all day, so I oblige. She fires questions at me. "Could I try it on?" No. "Is it uncomfortable?" Yes. "Do you sleep in it?" No. Then she says: "Oh, you must be very, very religious." I'm not sure how to respond to that, so I just walk away.

At the mosque, hundreds of women sit on the floor surrounded by samosas, onion bhajis, dates, and Black Forest gateaux, about to break their fast. I look up and down every line of worshippers. I can't believe it — I am the only person wearing the niqab. I ask a Scottish convert next to me why this is.

"It is seen as something quite extreme. There is no real reason why you should wear it. Allah gave us faces and we should not hide our faces. We should celebrate our beauty."

I'm reassured. I think deep down my anxiety about having to wear the niqab, even for a day, was based on guilt — that I am not a true Muslim unless I cover myself from head to toe. But the Koran says: "Allah has given you clothes to cover your shameful parts, and garments pleasing to the eye: but the finest of all these is the robe of piety."

Endurance test

I don't understand the need to wear something as severe as the niqab, but I respect those who bear this endurance test — the staring, the swearing, the discomfort, the loss of identity. I wear my robes to meet a friend in Notting Hill for dinner that night. "It's not you really, is it?" she asks.

No, it's not. I prefer not to wear my religion on my sleeve ... or on my face. —

© Guardian Newspapers Limited 2006

October 24, 2006

Sweden's Muslim Minister of Integration to ban Niqab for girls under 15 years of age. Nyamko Sabuni “I am neither a hard-liner nor an Islamophobe”

October 24, 2006

October 24, 2006 A small strip of cloth symbolizing Islamic separateness

Muslim groups are outraged. They want the hard-line minister dismissed. This could be difficult, because she is herself a Muslim immigrant — a striking woman from Burundi named Nyamko Sabuni. “I am neither a hard-liner nor an Islamophobe,” she says. “My aim is to integrate immigrants.”

In Britain, the storm over veils has been headline news for more than two weeks. Tensions are so high that Trevor Phillips, head of the government's Commission for Racial Equality, is warning that any further provocation could trigger the worst race riots in years. In his view, the debate has spun out of control. “This is an argument which is entirely about a very small strip of cloth,” he said yesterday, speaking to a Toronto diversity conference by audio phone. He was supposed to show up in person, but he cancelled his trip because of the emergency.

Many people argue that it is. After all, we manage to put up with all kinds of diversity. If a gay leatherman can roam around in straps and studs (as one gay leatherman argued in this newspaper's Letters page), then why get fussed over a few women who decide to cover?

The reason to get fussed is that the veil — specifically the niqab, which leaves only the eyes uncovered — has crystallized the issue of Islamic separateness. For many people, it stands for the deliberate rejection of Western norms. They argue that it is a political symbol as much as a religious one. And so it has become a lightning rod for the many stresses and woes of newly multicultural Europe.

Just three years ago, Britons who argued that Muslims must fit in were eviscerated by the likes of Mr. Phillips. Today, even he is arguing that Britain needs an urgent debate over its historical support for cultural separateness. “For 40 years, we've avoided discussing these issues because we've been too afraid of them.” He warns that Britain is “sleepwalking into segregation” as Muslim immigrants and their children lead lives increasingly isolated from the mainstream.

"Using the language of tolerance to justify oppressive practices is a grotesque perversion of liberalism.The veiling debate is a case in point"

Women and Islam

"...using the language of tolerance to justify oppressive practices is a grotesque perversion of liberalism. The veiling debate is a case in point. No amount of rhetorical sleight of hand can disguise the fact that the full-face veil makes women, literally, faceless. Some Muslim women in the West may choose this garb (which is not mandated in the Koran), but their explanations often reveal an internalized misogynistic view of women as creatures whose very existence is a sexual provocation to men. What's more, their choice helps legitimize a custom that is imposed on millions of women around the world who have no choice."

By Cathy Young

The Boston Globe

The niqab controversy has focused on thorny questions of cultural integration and religious tolerance in Europe. However, it is also a debate about women and Islam.

For Westerners, the veil has long been a symbol of the oppression of women in the Islamic world. Today, quite a few Muslims regard it as a symbol of cultural and religious self-assertion and reject the idea that Muslim women are downtrodden. In our multicultural age, many liberals are reluctant to criticize the subjugation of women in Muslim countries and Muslim immigrant communities, fearful of promoting the notion of Western superiority. At the other extreme, some critics have used the plight of Muslim women to suggest that Islam is inherently evil and even to bash Muslims.

Recently, these tensions turned into a nasty academic controversy in the United States, as the Chronicle of Higher Education has reported. In June, Hamid Dabashi, an Iranian-born professor of Iranian studies and comparative literature at Columbia University, published an article in the Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram attacking Azar Nafisi, Iranian émigré and author of the 2003 best seller ``Reading Lolita In Tehran." Nafisi's memoir is a harsh portrait of life in Iran after the Ayatollah Khomeini's Islamic revolution, focusing in particular on the mistreatment of women, who were stripped of their former rights and harshly punished for violating strict religious codes of dress and behavior.

Complaining that Nafisi's writings demonize Iran, Dabashi branded her a ``native informer and colonial agent for American imperialism." In a subsequent interview, he compared her to Lynndie England, the US soldier convicted of abusing Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib.

While Dabashi's rhetoric is extreme, it is not unique. Even in academic feminist groups on the Internet, criticisms of the patriarchal oppression of women in Muslim countries are often met with hostility unless accompanied by disclaimers that American women too are oppressed.

A more thoughtful examination of Islam and women's rights was offered earlier this month at a symposium at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. The keynote speaker, Syrian-American psychiatrist Wafa Sultan, an outspoken critic of Islam, described an ``honor killing" of a young Middle Eastern woman that occurred with the help of her mother. In a later exchange, another participant, Libyan journalist Sawsan Hanish, argued that it was unfair to single out Muslim societies, since women suffer violence and sexual abuse in every society including the United States. Sultan pointed out a major difference: In many Muslim cultures , such violence and abuse are accepted and legalized.

Yet the symposium's moderator, scholar Michael Ledeen, rejected Sultan's assertion that Islam is irredeemably anti-woman. He noted that the idea that some religions cannot be reformed runs counter to the history of religions. Several panelists spoke of Muslim feminists' efforts to reform Islam and separate its spiritual message from the human patriarchal baggage. Some of these reformers look for a lost female-friendly legacy in early Islam; others argue that everything in the Koran that runs counter to the modern understanding of human rights and equality should be revised or rejected. These feminists have an uphill battle to fight, and they deserve all the support they can get.

Meanwhile, using the language of tolerance to justify oppressive practices is a grotesque perversion of liberalism. The veiling debate is a case in point. No amount of rhetorical sleight of hand can disguise the fact that the full-face veil makes women, literally, faceless. Some Muslim women in the West may choose this garb (which is not mandated in the Koran), but their explanations often reveal an internalized misogynistic view of women as creatures whose very existence is a sexual provocation to men. What's more, their choice helps legitimize a custom that is imposed on millions of women around the world who have no choice.

Perhaps, as some say, women are the key to Islam's modernization. The West cannot impose its own solutions from the outside -- but, at the very least, it can honestly confront the problem.

---------------

Cathy Young is a contributing editor at Reason magazine. Her column appears regularly in the Globe.

October 20, 2006

New York based Pakistani columnist Khalid Hassan: Niqabi Muslim women in the West, "Exhibitionist and Deluded"

October 20, 2006

The Friday Times, Lahore

The utterly uncalled for insistence on donning the hijab and, of late, wearing the niqab, an attire more suited to the profession of banditry than anything I can think of, belittles Islam in whose good name it is being done. No sensible person can disagree with British politician Jack Straw who ended up putting his head into a hive of very angry bees when he said that he found it hard to communicate with a person whose face he could not see.

Neither the hijab nor the niqab has anything to do with Islam, as anyone who has taken the trouble to read the right texts and who is not smitten by that arch priestess of ignorance Dr Farhat Hashmi and her ilk would know.

Dr Fazlur Rahman suggested that all Quranic passages, revealed as they were at a specific time in history and within certain general and particular circumstances, should be given expression relative to those circumstances.

Another Muslim scholar, Dr Ibrahim Syed, has written that those who claim that Quranic verses are explicit about hijab, base that position on Surah Al-Ahzab (33:59). The operative words in Arabic on which this interpretation is based mean that women should `lower their garments' or `draw their garments closer to their bodies.'

Nowhere does the verse say that the face should be covered. Actually, the verse makes no mention of the word `face' Hijab advocates often quote Surah Al-Nur (24:31) to back their position.

According to Dr Syed, "In the pre-Islamic period, women used to wear a cloth called khimar on their necks that was normally thrown towards the back, leaving the head and the chest exposed.

The reference in Al-Nur apparently instructs that this piece of cloth, normally worn on the head and neck, should be made to cover the bosom. So it is erroneous to conclude that the Quran demands (of) Muslim women to cover their heads." Another Islamic scholar, Dr Abou el Fadl, says, "From the gross liberties taken in translating the (Quranic) text, apparently the translators believe that God wishes women to be like house-broken dogs – loyal, sweet and obedient.

One can only ponder what type of rotted and foul soul imagines that God wishes to imprison women in a sewer of squalid male egos, and suffer because men cannot control their libidos. What an ugly picture they have created of God's compassion and mercy!" A Western scholar of Islam, Daphne Grace , writes that the veiling of women is nowhere explicitly prescribed in the Quran.

Another scholar, Fadwa El Guindi, has said that the original meaning of the Quranic verse was to "cover the cleavage of the breasts." What the Quran forbade was the public flaunting of sexuality, with a parallel verse prescribing a modest dress code for men as well.

According to El Guindi, the original use of the veil was to distinguish the status and identity of the wives of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him) "so that they may be recognised and not molested." (The Quran, 33:59).

Fatima Mernissi, an Arab scholar, has written that the boundary between forbidden space, which is hidden by the hijab, and permitted space, became a key concept in the Islamic world, but "reducing or assimilating this concept to a scrap of cloth that men have imposed on women to veil them when they go out on the street is truly to impoverish this term, not to say drain it of its meaning."

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, the well-known London-based Muslim journalist, wrote in Time magazine on 16 October that it is "time to speak out against this objectionable garment and face down the obscurantists who endlessly bait and intimidate the state by making demands that violate its fundamental principles.

That they have brainwashed young women, born free, to seek self-subjugation breaks my heart. Trained creatures often choose to stay in their cages even when released. I don't call that a choice. I would not propose that Muslim women should be stopped from wearing what they choose as they walk down the street, although, to be sure, there are practical problems with the niqab. I have seen Muslim women who had been appallingly beaten and forced to wear it to keep their wounds hidden. Veiled women cannot eat in restaurants, swim in the sea or smile at their babies in parks."

The British-Muslim journalist supports the ban imposed by France on the hijab in public schools, noting that protests against the injunction soon died down and many Muslim French girls were happily released from a heritage that has no place in the modern world. Belgium, Denmark and Singapore have taken similar steps.

Noting that Britain has been both more relaxed about cultural differences and over-anxious about challenging unacceptable practices, she points out that few Britons have realised that the hijab – now more widespread than ever – is, for Islamicist puritans, "the first step on a path leading to the burqa, where even the eyes are gauzed over."

She goes on to write, "I have interviewed young women who say they feel so wanton wearing only a headscarf that they will adopt the niqab. Now even 6-year-olds are put into hijabs." She writes, "Western culture - it is true – is wildly sexualised and lacking in restraint. But there are ways to avoid falling into that pit without withdrawing into the darkness of a niqab. The robe is a physical manifestation of the pernicious idea of women as carriers of original sin; it assumes that the sight of a cheek or a lock of hair turns Muslim men into predators. The niqab rejects human commonalities.

The women who wear it want to observe fellow citizens, but remain unseen, as if they were CCTV cameras." Alibhai-Brown writes that as a modern Muslim woman, she fasts and prays, but refuses to submit to the hijab or to an "opaque, black shroud."

A Saudi Arabian woman lawyer said to her, "The Quran does not ask us to bury ourselves. We must be modest. These fools who are taking niqab will one day suffocate like I did, but they will not be allowed to leave the coffin." Millions of progressive Muslims want to halt this Islamicist project to take us back to the Dark Ages, Alibhai-Brown warns. Islamism is a negation of Islam and it must be resisted wherever one comes across it.

It is being carried to ridiculous limits, for example, in Iraq's Shia-controlled areas, where, according to a report in The Washington Post , long hair is banned because it makes men look feminine. Haircuts that are long on the sides and short on top, are forbidden because they are "Jewish" and Muslims are not allowed to "imitate Jews."

There is "hair police" on the prowl, one of whom said that if someone is judged to have an improper hairstyle, "we will take him to the barber and we'll ask the barber to cut his hair according to our regulations. If he refuses, we would send for his father or elder brother and tell them, `Either you take this measure or we'll take the measure for you'."

I think Iqbal, being the seer he was, got it right: Ye Ummat khurafat mein kho gayee (The body of the faithful got lost in delusions).

October 19, 2006

Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi tells Muslim women: "You can't cover your face ... you must be seen"

behind veil: Italian PM

'You can't cover your face ...

you must be seen,' Prodi says

"You can't cover your face. If you have a veil, fine, but you must be seen," Prodi said, adding: "This is common sense I think, it is important for our society. It is not how you dress but if you are hidden or not." British Prime Minister Tony Blair also weighed in yesterday, calling the Muslim veil a "mark of separation and that's why it makes other people from outside the community feel uncomfortable."

Blair said he did not want to ban the veil. "I'm not saying anyone should be forced to do anything," he told his monthly news conference. "No one wants to say that people don't have the right to do it. That's to take it too far. "But I think we do need to confront this issue about how we integrate people properly with our society and all the evidence is when people do integrate more they achieve more as well."

Prodi, a centre-left leader, and former head of the European Commission, echoed controversial remarks made earlier this month by Straw. Straw said veils had acted as "a visible statement of separation and difference."

Like Britain, Italy does not specifically restrict the wearing of the veil, but it has in the past had laws against covering your face in public for security reasons. France, however, has a law banning "conspicuous symbols" of faith such as Muslim headscarves, Jewish skullcaps and large Christian crosses, from schools. Prodi has angered the centre-right opposition, led by former premier Silvio Berlusconi, with an immigration policy that proposes to halve an application period for Italian citizenship to five years, in exchange for observation of Italian laws.

"The problem is to have clear rules, so that if they behave, if they respect the law, if they are good citizens, they can become Italian citizens," Prodi said. Opinion polls show immigration is the top concern for voters on the centre-right in Italy, which was very narrowly defeated by Prodi in April's elections.

But Prodi said it was "a problem not just for right-wing voters, it is a problem for everybody ... because for the first time a country that was a country of emigration is a country receiving a wave of immigrants."

But he contrasted his own policy with that of the Berlusconi government, a coalition that included the hard-right Northern League, which traditionally takes a tough stand on immigrants. "

The right-wing policy was to close their eyes and let immigrants come in, (but) be very restrictive in theory. My policy is let us guide immigration, guarantee immigrants their rights and try to be realistic about this flow of people."

Italy and some of its southern European neighbours will propose a common EU immigration policy at a summit in Finland later this week, Prodi said, with a decision hopefully to be taken at a later summit in Brussels in December.

October 14, 2006

Raheel Raza: "Let's Pull the Veil off our Minds"

October 14, 2006

October 14, 2006Muslims are at risk of ghettoizing ourselves

By Raheel Raza

Britain’s Cabinet Minister Jack Straw took a risk with his political future (his riding is predominantly Muslim) by his suggestion that Muslim women should consider removing the veil from their face.

Instead of a knee jerk reaction, Muslims should accept Mr. Straw’s comments at face value, take our heads out of the sand and pull the veils off our minds. His intention was to invoke a debate, not start fireworks!

This dialogue is long overdue and it comes at a critical time for Muslims in the West. Unfortunately some ignorant and bigoted people have misused this situation to vent their angst at Muslims (e.g. the person who pulled the veil off a woman’s face in England ) and others will use it as a political tool and this has to be addressed.

For better understanding of the issues at stake, let me start the discussion.

Contrary to some peoples view, covering the face is not a religious requirement for Muslim women. The injunction in the Quran is for modesty (for both men and women). Some Muslim women interpret this as covering their head with a scarf or chador,

My understanding of this stems from the fact that Islam is a religion of balance and reason. Our face is our identity and common sense requires for it to be uncovered. Furthermore, Muslim women are not supposed to cover their face when they go for Haj (pilgrimage) or when they perform the obligatory prayer.

Of the 1.2 billion Muslims in the world spread over the globe from Malaysia to Mozambique, approximately half are women who are extremely diverse in their mode of dress. A very small percentage chooses to cover their face.

In parts of the Middle East and the subcontinent, a face covering or niqab, is prevalent as a cultural or tribal norm. Some women have exported this practice to the Western world.

If this is cultural, then there is dire need for discussion about adapting to new cultures. Cultures evolve and change with time and place. When non Muslims travel to Saudi Arabia for example, they’re not allowed to expose skin by wearing shorts or skirts. The Committee for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (CPVPV) will arrest them. Many Westerners work and reside in Saudi, so they adapt to the new culture to make life easier for themselves.

Similarly when we come to West by choice, we adapt to many changing factors without compromising our religious beliefs. In Canada the Charter gives us religious freedom to practice our faith in any way we choose. However, we need to let go of excess cultural baggage.

Mr. Straw suggested that a covered face makes communication difficult. He’s right. I just saw a video interview of a woman in England on this issue, and her voice was muffled from behind the veil. Furthermore, in Canada there is current discussion in the judicial system about the safety risk of a woman who wants to drive in a burqa because peripheral vision becomes impaired. A covered face is also an identity issue while traveling.

Of course it’s a given that women in the West have the right to wear as little or as much as they want. But let’s talk about the larger issue.

It’s a common perception that people who wear masks have something to hide. Muslim women on the other hand, have a lot to show for the strides they’ve made in the modern world. They were given freedom and rights 1400 years ago. Today Muslim women are traveling into space and winning nobel peace prizes. So why the need to hide?

Perhaps this is symptomatic of a larger issue. For the sake of future generations in the West, we must understand that we are at risk of ghettoizing ourselves and being labeled “the other” if we don’t get with the plan and work towards being the mainstream. If we insist that we can’t change, then we’re entirely to blame when we remain on the fringes of society.

Islam encourages us to progress with time, to reason and adapt to current situations without compromising our faith. By showing our face, the faith is not compromised.

This is my perspective. Let’s begin the debate.

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown declares in TIME Magazine: "It's not illiberal for liberal societies to disapprove of the veil"

Sunday, Oct. 08, 2006

Feminists have denounced Straw's approach as unacceptably proscriptive, and reactionary Muslims say it is Islamaphobic. But it is time to speak out against this objectionable garment and face down the obscurantists who endlessly bait and intimidate the state by making demands that violate its fundamental principles.

I would not propose that Muslim women should be stopped from wearing what they choose as they walk down the street, although, to be sure, there are practical problems with the niqab.

The example of France is salutary here. In 2004, the government banned the hijab, the headscarf, in public schools. The policy may have been introduced with an air of insufferable Gallic superiority, but it was absolutely right; overtly religious symbols are divisive.

Western culture — it is true — is wildly sexualized and lacking in restraint. But there are ways to avoid falling into that pit without withdrawing into the darkness of a niqab. The robe is a physical manifestation of the pernicious idea of women as carriers of original sin; it assumes that the sight of a cheek or a lock of hair turns Muslim men into predators.

As a modern Muslim woman, I fast and pray; but I refuse to submit to the hijab or to an opaque, black shroud. On Sept. 10, 2001, I wrote a column in the Independent newspaper condemning the Taliban for using violence to force Afghan women into the burqa. It is happening again.

In Iran, educated women who fail some sort of veil test are being imprisoned by their oppressors. Saudi women under their body sheets long to show themselves and share the world equally with men.

Exiles who fled such practices to seek refuge in Europe now find the evil is following them. As a female lawyer from Saudi Arabia once said to me:

"The Koran does not ask us to bury ourselves. We must be modest. These fools who are taking niqab will one day suffocate like I did, but they will not be allowed to leave the coffin."

Millions of progressive Muslims want to halt this Islamicist project to take us back to the Dark Ages. Straw is right to start a debate about what we wear.

Prof. Mohammad Qadeer: "Concealment of the face is neither religiously necessary nor socially desirable"

March 27, 2006

March 27, 2006 Masking the truth

By Prof. Mohammad QadeerQueen's University, Kingston

Globe and Mail, Toronto

If you live in New York, London, Toronto or other cities of Europe and North America, you may have seen an occasional woman with the niqab, the face veil that conceals most of the face except the eyes.

The face veil has been appearing in the public space of Western cities since the 1990s, coinciding with the rising consciousness of Islamic identity.