March 27, 2006

March 27, 2006 Masking the truth

By Prof. Mohammad QadeerQueen's University, Kingston

Globe and Mail, Toronto

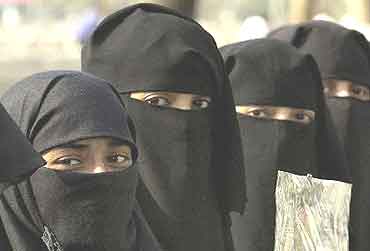

If you live in New York, London, Toronto or other cities of Europe and North America, you may have seen an occasional woman with the niqab, the face veil that conceals most of the face except the eyes.

The face veil has been appearing in the public space of Western cities since the 1990s, coinciding with the rising consciousness of Islamic identity.

Amidst throngs of women in body-revealing clothing, seeing a woman with her face concealed and her eyes peeping out of the wraparound veil is surprising. Though I grew up in a Muslim country, the first time I saw a woman clad in the niqab was in Montreal in 1997. It was an odd sight for me. I could not help doing a double take, asking myself "here of all places?"

I have known the burka, a head-to-feet coverall made notorious by the Taliban. It covers the eyes, too, with a thin see-through material. My mother at one time wore a burka, though she discarded it when her daughter refused to don one, and as the custom was fast disappearing from urban Pakistan. I knew the niqab from the fable of the Arabian Nights.

Understandably, seeing it on a live person in downtown Montreal was odd, if not shocking, particularly after decades of living in North America.

The niqab is beginning to cause some public concerns in Europe. The city of Maaseik, Belgium, has banned it from public places. Other towns in Belgium and Holland are contemplating similar actions. There are some questions of common interest that arise from the spread of this custom in Western societies.

The niqab should be differentiated from the hijab, which is just a scarf tied around the head, leaving the face completely visible. The hijab has religious and cultural antecedents in Europe. It is like the traditional head scarf of women in Italy, Greece or Russia.

The niqab is another matter. It is a statement of women's self-concealment. Those who wear it consider it to be their religious obligation.

The argument about concealing one's face as a religious obligation, is contentious and is not backed by the evidence. Muslim women all over the world overwhelmingly do not wear either the niqab or the burka.

There was never a time in Muslim history, not even in the early days of Islam, when a majority of women covered their faces. It was only the practice of some tribes, small orthodox sects and women of the ruling elite. Recent evidence from impromptu TV shots of the tsunami devastations in Indonesia, earthquake victims in Pakistan, street crowds in Palestine, Iraq or Egypt, seldom show any women wearing the niqab.

Rural women and women workers in cities have always gone about with their faces visible. The niqab has been the luxury of some puritanical and leisured families. Yes, in conservative and tribal cultures of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia or parts of the Gulf, women conceal their faces. Yet even in these countries, a slight reduction of social pressures brings out large numbers of women without face veils.

Even doctrinal Islam has no unanimity about a woman covering her face.

For centuries, arguments have raged about the body covering that are obligatory for women's modesty in Islamic society. Those advocating a woman concealing her face are a small and orthodox minority of Islamic scholars and jurists.

In Western societies, the niqab is also an assertion of Muslim identity in an environment of felt discrimination. Yet this choice has social implications especially for those living in pluralist societies. From driving or cashing a cheque to boarding a plane, there are a host of activities requiring photo identity, for example. The niqab has led to awkward confrontation in such situations.

In Western societies, the niqab also is a symbol of distrust for fellow citizens and a statement of self-segregation. The wearer of a face veil is conveying: "I am violated if you look at me." It is a barrier in civic discourse. It also subverts public trust.

Yet the primary victims of the niqab are its wearers. A prospective employer may be justified in not hiring someone whose facial expressions are unavailable to those communicating with her, be they customers, coworkers or the general public.

Similarly, the educational experience of a woman clad in the niqab is compromised because of her visual segregation from fellow students, teachers and team members. The niqab necessitates awkward and costly accommodations for its wearers in offices and schools. It has social and personal costs.

In pluralist and democratic societies, women have won equality after a long struggle. The niqab is a symbol of self-inflicted inequality and exclusion. Someone may argue that it is a right of an individual to wear what she likes. Yet all rights have limits. Your right to conceal your face infringes others' right to know who you are.

Muslim women living in the West can practise modesty with the hijab or in other suitable ways that allow the face to be visible. Concealment of the face is neither religiously necessary nor socially desirable. Muslim communities should reappraise this custom, before a scare about terrorists or a bank hold up raises a public uproar against the niqab.

1 comment:

I don’t commonly reply to content but I'll in this situation. Wow

Post a Comment