October 24, 2006

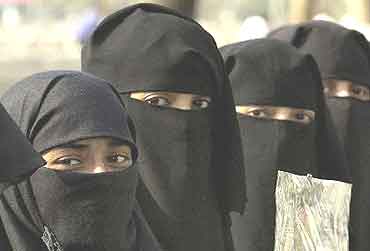

October 24, 2006 A small strip of cloth symbolizing Islamic separateness

In progressive, tolerant Sweden, now home to 300,000 Muslims, the times are changing. The tough new message for immigrants: Learn Swedish and get a job. The new minister of integration and equality wants a ban on veils for girls under 15 (the Swedish age of consent), and wants adolescent girls to be examined for signs of genital mutilation so that the perpetrators can be prosecuted. Meantime, the state-funded Centre Against Racism has lost its funding.

Muslim groups are outraged. They want the hard-line minister dismissed. This could be difficult, because she is herself a Muslim immigrant — a striking woman from Burundi named Nyamko Sabuni. “I am neither a hard-liner nor an Islamophobe,” she says. “My aim is to integrate immigrants.”

In Britain, the storm over veils has been headline news for more than two weeks. Tensions are so high that Trevor Phillips, head of the government's Commission for Racial Equality, is warning that any further provocation could trigger the worst race riots in years. In his view, the debate has spun out of control. “This is an argument which is entirely about a very small strip of cloth,” he said yesterday, speaking to a Toronto diversity conference by audio phone. He was supposed to show up in person, but he cancelled his trip because of the emergency.

Is the fight over the veil just a flimsy issue blown out of all proportion?

Many people argue that it is. After all, we manage to put up with all kinds of diversity. If a gay leatherman can roam around in straps and studs (as one gay leatherman argued in this newspaper's Letters page), then why get fussed over a few women who decide to cover?

Many people argue that it is. After all, we manage to put up with all kinds of diversity. If a gay leatherman can roam around in straps and studs (as one gay leatherman argued in this newspaper's Letters page), then why get fussed over a few women who decide to cover?

The reason to get fussed is that the veil — specifically the niqab, which leaves only the eyes uncovered — has crystallized the issue of Islamic separateness. For many people, it stands for the deliberate rejection of Western norms. They argue that it is a political symbol as much as a religious one. And so it has become a lightning rod for the many stresses and woes of newly multicultural Europe.

Just three years ago, Britons who argued that Muslims must fit in were eviscerated by the likes of Mr. Phillips. Today, even he is arguing that Britain needs an urgent debate over its historical support for cultural separateness. “For 40 years, we've avoided discussing these issues because we've been too afraid of them.” He warns that Britain is “sleepwalking into segregation” as Muslim immigrants and their children lead lives increasingly isolated from the mainstream.

And sometimes, he acknowledges, it is they who must change. Last week, for example, an employment tribunal ruled that a teaching assistant must remove her veil in class because the children need to see her face in order to learn English. Mr. Phillips supported the decision. “I think she would be doing the nation a favour not to appeal,” he says.

Nobody should be particularly surprised by Europe's growing ethnic tensions. People are inherently tribal, and building trust and common norms across tribal lines is hard. And there's a big difference between today's immigrants and those of a century ago. In the past, immigrants knew they had to fit in because they could never go home. For today's immigrants, home is just a plane ride away — and they can stay connected to their tribe forever.

A decade ago, political scientist Robert Putnam described America's waning social cohesion in the bestselling book Bowling Alone. Now he has turned his research to diversity and multiculturalism — and his findings are sobering. Ethnic diversity, he has found, breeds mistrust. Communities where many ethnicities live together have lower amounts of trust between people than those that are more homogeneous. “In the presence of diversity, we hunker down,” he writes. “The effect of diversity is worse than had been imagined.”

Mr. Putnam is quick to stress that trends aren't destiny, and there's plenty that can be done to make diversity work. But whether that diversity should include the veil is not an issue that will be settled soon. In Italy, which now has a million Muslims, Prime Minister Romano Prodi declared last week that in his opinion, women shouldn't wear veils that hide the face.

Then a leading conservative politician named Daniela Santanchè weighed in, arguing that the veil is a symbol of female oppression and is not required by the Koran. A prominent imam lashed back, calling her an “infidel” and much else.

Ms. Santanchè has now been offered police protection.

No comments:

Post a Comment